“He’s quick, and he’s good.” That’s how athletes like Michael Jordan described Walter Iooss Jr. “These words are [the] ‘biggest compliment,’” said Iooss Jr., who knew how hectic sports stars’ schedules were. “Because that’s what you had to be. And the word gets out.”

That instinct was shaped long before he ever held a press pass, when he was just starting out in New Jersey. “When I was a kid, my mind was always thinking about sports. It was just nonstop,” said Iooss Jr., who was born and raised in EastOrange. When he was young, after his parents divorced, he’d visit his father, Walter Iooss Sr., in Brooklyn on Sundays. Iooss Sr. was a jazz musician with a love for photography, and in the late ’50s, he bought an Asahi Pentax and season tickets to the New York Giants. From their high seats, Iooss Sr. would snap photos, sometimes to the annoyance of fans behind him. At first, Iooss Jr. wanted no part of it—until he got curious. At 15, he took four photos, developed a roll, held it up to the light, and something clicked. “That was it,” he said. “My future was unlocked.”

Soon, he began voraciously taking pictures of his friends. His father began driving him to photo shoots like it was basketball practice. At 16 years old, after cold-calling a photo editor at Sports Illustrated, he landed his first assignment with the magazine. A year later, he was officially hired two weeks to the day after graduating high school.

“My first big assignment was Game 7 of the 1962 Los Angeles Lakers and Boston Celtics playoffs,” he said. “I usually shot two or three rolls, but that night I shot over 20—and took some of the best photos of my life,” said Iooss Jr. “From that moment on, I was in.”

Since then, Iooss Jr. has become a cultural hitchhiker of sorts, riding shotgun fthrough different eras of sports and documenting its history through images that helped shape how the world sees greatness—from Jordan to Kobe Bryant andSerena Williams; Tiger Woods to LeBron James; Muhammad Ali, Tom Brady, Usain Bolt and Michael Phelps.

Over the years, his technique has evolved, too. “Initially, I was focused on capturing action,” said Iooss Jr. “But I got tired of the standard positions under the basket, and I became more interested in backgrounds and unique angles.”

Iooss Jr. believes that the key is to have your eyes drawn to one element in the picture, but that everything, from the background to the composition to the athlete’s eyes, composes the whole of a great photo.

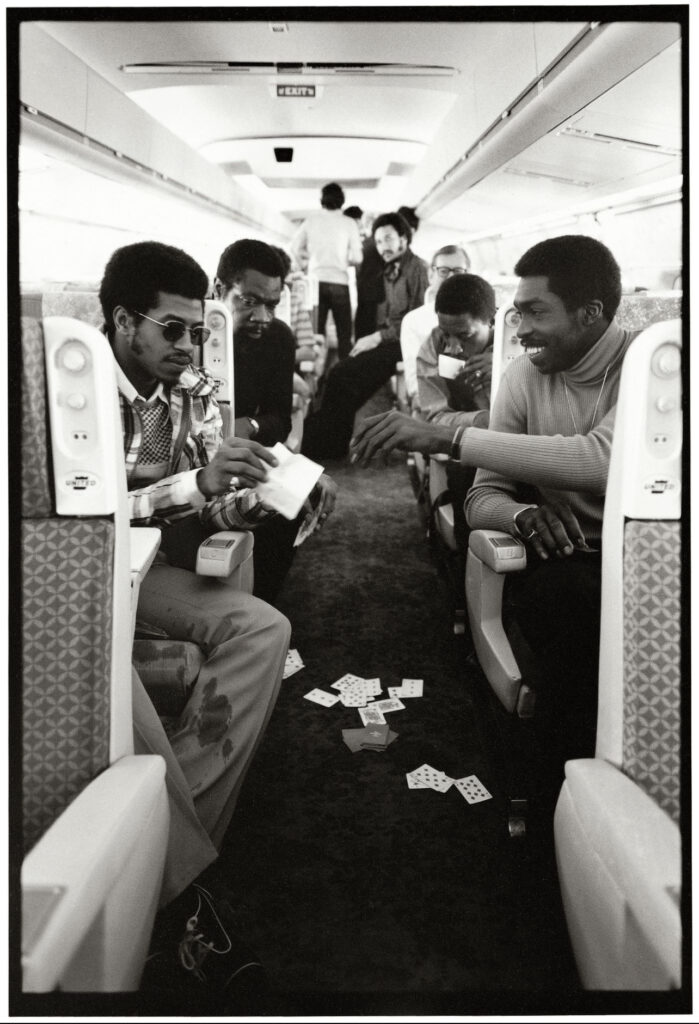

In today’s social media era of scrolling Instagram’s or TikTok’s algorithm-fueled deluge of content, his images can still stop a person cold. Not because they’re engineered for engagement, but because they capture something elusive: heroes frozen at the apex of their superhuman powers, like Jordan’s winning NBA slam dunk in 1988. Images like these can remind us of our human potential. Or we see ourselves in their intimacy, like in the contemplative photos of Bryant deep in thought riding a bus or smiling while walking the streets in civilian clothes.

Yet, Iooss Jr.—described by Sports Illustrated as poet laureate of sports photography—isn’t done. This fall, he’s launching a book with Taschen of candid Michael Jordan photographs. “We scanned all the great images of Jordan. And Jordan will never die—he’s like a biblical figure in sport, like Ali, Babe Ruth, etc.,” said Iooss Jr.

We talked to Iooss Jr. about why he was sick of three-point shots, how he got the most famous image of Jordan dunking and what it takes to be the best.

Robert Cordero: What is it about sports that gets you? And why do you think so many people are drawn to it in general?

Walter Iooss Jr.: It’s an escape in many ways. When you’re playing baseball or stick ball, a sport I loved, the moment that the pitch is delivered to you, there’s nothing else in the world that matters. It’s the same thing when you release your jumper. There’s so much joy in sport.

RC: That photo of Michael Jordan’s dunk in ’88 has become one of the mosticonic images in all of sports. What did it feel like to witness—and capture—history in real time?

WI: Let me take you back to the year before, when I went to the slam dunk contest in Seattle. There were a lot of good dunks, but I learned if you can’t see the face of the guy dunking, the picture is worthless. So in 1988, I went to the stadium in Chicago on that cold day, three, four hours before the contest. There’s Michael, sitting in the first row. I said, “Mike, I’m going to ask you something. It’s either the dumbest question or the smartest question.” I said, “Michael, is there any way you can tell me which way you’re going to go so I can get your face in the picture?” He looks at me, says yeah. I said, “Well, how are you going to do that?”He said, “You look at me at the bench, and I’ll point my finger on my knee.” That slam dunk is the last dunk he did. The previous dunk was the same type of dunk, where he took off from the opposite of the court, and I positioned myself leaning against that cushion under the basket, straight under the basket, and he landed in my lap, which was sort of fun, but I don’t think he liked it that much. So the last dunk, I’m in the same spot, and he looks down the court, and he waves his hand, telling me to move to my right, and then in one frame, that slam dunk was born.

RC: In the annals of sports photography, Rare Air is one of the most seminal books ever published. Michael Jordan is famously private—how did you earn his trust to create something so personal, so revealing?

WI: In 1992, during a slow year, I was inspired by photo essays like the one on Elvis in ’56 and the Clintons in Time magazine. I flew to Chicago unannounced and waited in the locker room, where Michael was always the last one to leave after interviews. When he came out, I said, “Hey, Mike.” He asked, “What are you doing here?” I told him I had an idea, and he responded, “Your ideas usually mean work.” I explained the concept of creating an intimate photo album that could stay in his family forever. I showed him pictures I’d taken of him, and he liked how I made him look. We met again a week later in Los Angeles, where he said he liked the idea. We shook hands with no contract, and the book was born. The cover was a serendipitous moment.

RC: And that cover showed Michael in a way we’d never seen before. How did that come together?

WI: When I was in Chicago, I stayed at the Ritz-Carlton there and they always had these white robes. Outside, there was a newsstand—when there used to be newsstands out there—and there was a cover of someone from the Middle East in a white robe with the hood up in profile; it was so beautiful against the white background. So I was like, “I should ask Michael to put this robe on.” So when I went to his hotel in Coconut Grove, we went up to the roof. Amazingly enough, he had this white wall with the slopes in the background. I had the lifeguard hold an umbrella over his head, and we took 10 frames, and that became the cover of Rare Air.

RC: You’ve spent some time with LeBron James—what were some of your favorite moments or stories from that experience?

WI: My first shoot was LeBron, still one of my best. I think I came in with an 8-by-10 camera up to Cleveland. He was 17. It was his rookie season. The PR guy walks in, and I said,“How much time do I have?” He said, “You have 10 minutes.” I said, “When does it start?” He says, “The moment he walks in the room.” I’ve always believed I’d rather waste three minutes of the time—and I never go over time, unless they give it to me—to at least speak to the person, show them something I’ve done before, [something about] the picture I want to take, so I’m down to seven minutes. You know, I do some two-and-a-quarter stuff, and I do a few 8-by-10 Polaroids—bingo.

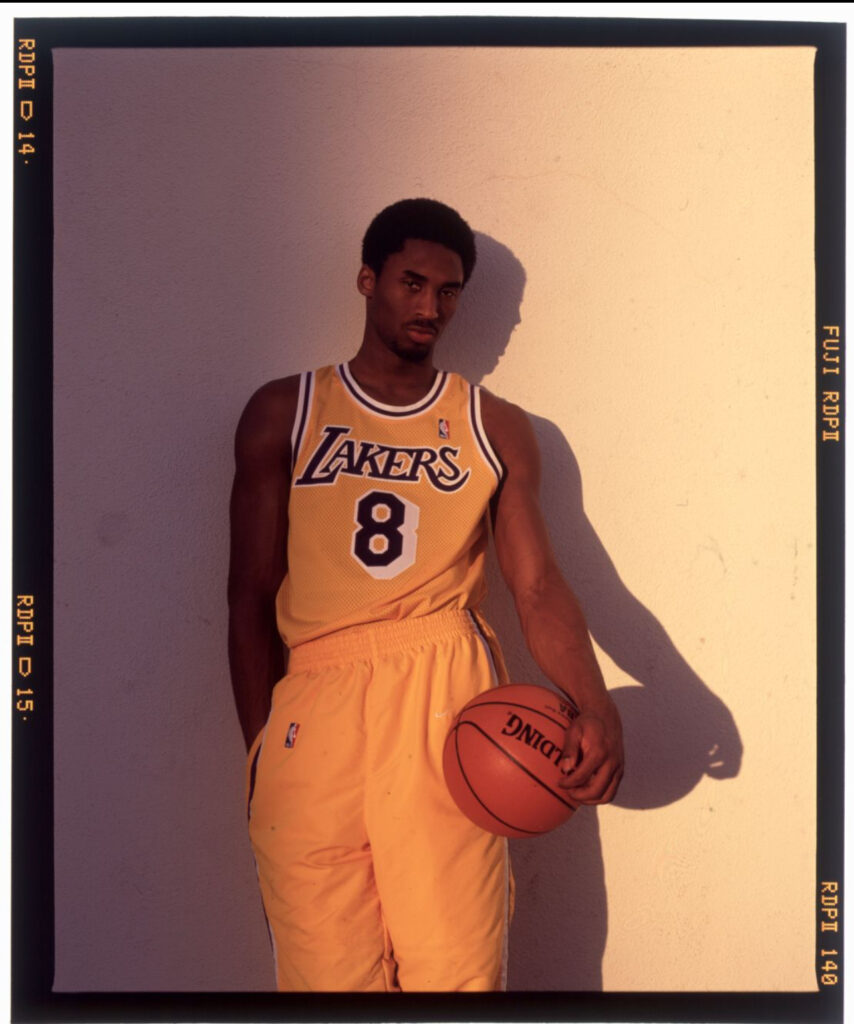

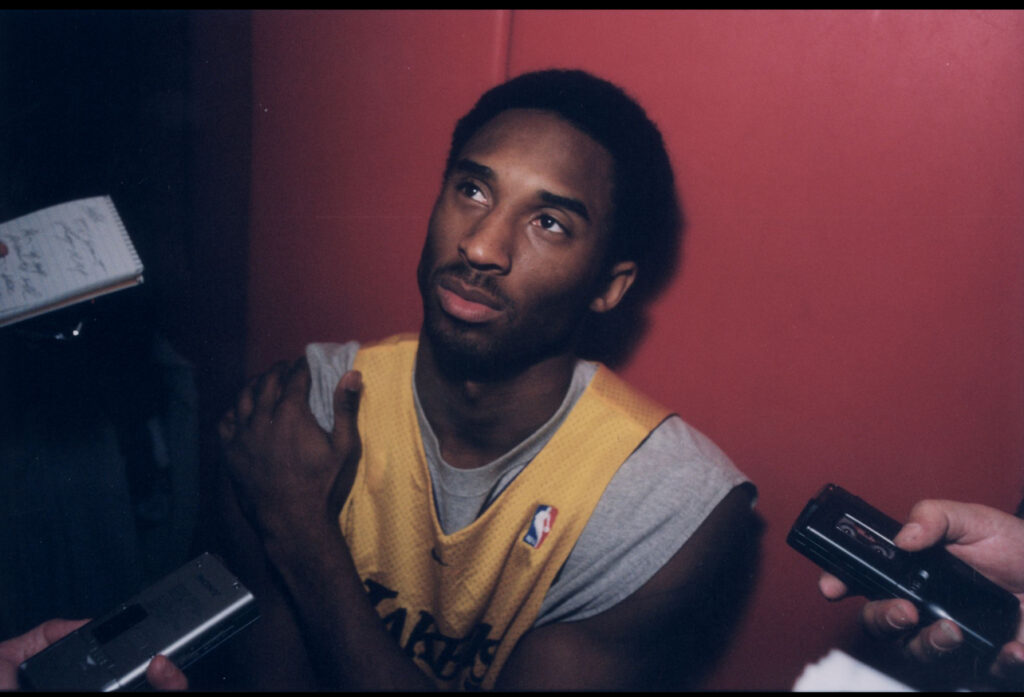

RC: You’ve photographed many legends, but Kobe Bryant had a presence all his own. Do you have any memories from shooting him—anything that stuck with you?

WI: He was a very special guy. When we were doing a project together, I flew in that chopper back and forth. I mean, his commute to the stadium where he lived was just too far, an hour and 45 minutes each way, so he took a chopper. I remember exactly where I was when it happened. I was in Scottsdale, Arizona, and then I had to go to my room for a while. It was very upsetting. He was such a talented man. He won an Oscar. He was interested in art. He spoke fluent Italian.

RC: What have you learned by being surrounded by these athletes?

WI: Well, to be a good athlete, you’ve got to be prepared, and you’ve got to be focused. You’ve got to play hard.

RC: How has NBA basketball changed from when you first started photographing the sport?

WI: I’m tired of the three-point shot. It’s nice to see it sometimes, but when you look at the box scores, and I look at how many three-pointers a team will take, they take 52 three-point shots with 24%. I like it when they move the ball. That’s one thing with the college game, they moved the ball a little better, and the women’s game (NCAA championship), there were so many plays inside. I think the level of athleticism and training and size, you know, just looking, people are bigger than they used to be 20 years ago. You’re raising athletes that are playing at such incredible levels, and it’s just an evolution of a game.

RC: Sports is so global and big now. People want to photograph athletes. What can they learn from you?

WI: Listen, if you love something and you’re good at it, you’ve got to work at it. I started very young, but I don’t think there’s a business out there for it like the reused to be. There are still options, but they’re very narrow. But if you want to try to do something, I think you have to have talent. You have to see and feel things. I was possessed with photography at 13. I was so possessed with sports, in sports magazines. I was always possessed with the form of the athlete, of where the body is. It’s the dedication—you can’t half-ass it if you want to make it. There are no options.

RC: How do you engage with sports photos these days?

WI: I have prints from other photographers. I need images around me all the time. Our house in Montauk is like the easternmost art gallery—there are a lot of famous prints in there. I still can’t live without images.